Clément Cogitore’s Braguino or The Impossible Community, winner of Le Bal’s first Award For Young Creation, realised as an immersive exhibition of photography, film and sound. The second edition of the Biennial of Photographers of the Contemporary Arab World at M.E.P. and seven other venues across the city. Noémie Goudal’s latest series, Telluris, created last spring in the Californian desert, complete with an on-site installation at Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire. Raymond Depardon’s Traverser retrospective at the Fondation Cartier-Bresson, Albert Renger Patzsch at the Jeu de Paume, Malick Sidibé’s Mali Twist at Fondation Cartier…

With so much to see condensed into one city over the course of five days during Paris Photo (09-12 November), you’d be tempted to skip round the 149 galleries lining the elegant, glass-topped halls of the Grand Palais in a couple of hours, or even miss the main event altogether, as many do. That would be a mistake. You won’t get a better snapshot of what constitutes saleable photography in 2017, from the blue-chip North American dealers such as Gagosian, Pace MacGill and Howard Greenberg, to the work of younger artists championed by the likes of Project 2.0, Trapéz and Taik Persons. And eavesdropping on the sales patter can be a real an eye-opener.

The galleries are selected from around 300 applications, chosen on the strength of what they propose showing at the fair, the Paris Photo directors Florence Bourgeois and Christoph Wiesner tell me in an interview in London in mid-September, and their determination “to show the entire production of the existence of photography, from the beginning until now”. The historical scope takes in everything from Lewis Carroll and Hill & Adamson at Hans P Kraus, to the fair’s collaboration with the Picto Foundation and SNCF to show the work of four recent European graduates – two of which, William Lakin and George Selley, are from British colleges.

![]()

From Telluris, 2017 © Noémie Goudal, courtesy Galerie Les Gilles due Calvaire Paris Photo

‘Vintage modernes’, from the likes of Alexey Brodovitch at Howard Greenberg, Edward Weston at Edwynn Houk, and Ilse Bing at Karsten Greve – though they are no longer the bargain they were when the fair began 21 years ago. The geographical spread includes strong representation from Asia, with galleries such as Tokyo’s NAP gallery selling key works from Shomei Tomatsu and Mao Ishikawa, or M97 from Shanghai, who’ll be bringing over Wang Ningde’s remarkable, process-driven Forms of Light series created with the aid of projection software, which is quite a departure from Some Days, the 10-years-in-the-making work he’s best known for, capturing the tension and detachment wrought by the rapid changes in his birthplace in Liaoning province.

And there are the galleries that you can always turn to to find something interesting: South Africa’s Stevenson gallery with new work from Guy Tillim; Zurich dealer Christophe Guye showing Rinko Kawauchi’s latest series, Halo; Doha’s East Wing with Katrin Koenning.

Rather than retreating against the encroachment of the digital sphere, not to mention economic and socio-political strife (the 2015 edition closed in the aftermath of the Paris terrorist attacks), the fair is thriving. “Last year we had 62,000 visitors in five days,” says Bourgeois, Paris Photo’s director in charge.

But why do we even need fairs in this day and age, where all these works can be seen online, and collectors already have close relationships with the dealers? “It is a place to meet. You can see that Paris Photo is an international rendezvous,” she answers.

“For the visitors and collectors and galleries, it is tremendously important to be in a fair, because it is there that they can achieve very high visibility. It’s strange to see that in Paris and elsewhere, like New York, the galleries are empty in the middle of the week… they need fairs for visibility and to meet the public – not only the collectors, but the newcomers. And photography is a very good point of entry for a collection. So, meeting a general audience can also lead to sales.”

![]()

From the series Astres Noirs © Katrin Koenning

The move to the Grand Palais in 2011, was a kind of confidence trick, according to former director Julien Frydman, who masterminded the move – a show of confidence to the wider art market that a photography fair could thrive in one of the world’s most prestigious exhibition halls. “We had this switch when we moved to the Grand Palais,” says Bourgeois.

“So now around 60 percent of the galleries are contemporary, with artists who work in many styles and mediums. Of course, when you have contemporary galleries, you have collectors of contemporary [art] coming.”

But it’s a slow process, she and Wiesner, the artistic director, admit. Which is why they’re so focused on improving the fair with an ever-expanding programme. Wiesner’s main contribution towards this, after the pair arrived in 2015, was to introduce Prismes, using the upstairs galleries of the Salon d’Honneur to create a space “dedicated to serial artworks, large formats, and installation and performance projects that open up new fields of exploration of images across all forms”, many nominated by participating galleries.

“It’s not traditional scenography,” says Bourgeois, meaning that it’s more ambitious in terms of scope and curation than conventional fair booths will allow. “We are committed to it, and now it’s positive to see that galleries are presenting projects by themselves.”

There are 14 works or series in total, but there’s one that Wiesner is clearly excited about, presented by Cologne-based Thomas Zander gallery, as he mentions it several times. “US 77 is a key work for [Sheffield-born] Victor Burgin because it’s when he started to introduce text with images, like a glossy magazine. On the opposite side we have a project by Klaus Rinke, a mutation with these 112 faces – a self-portrait. It’s interesting because he was one of the first to introduce photography into his performance practice.

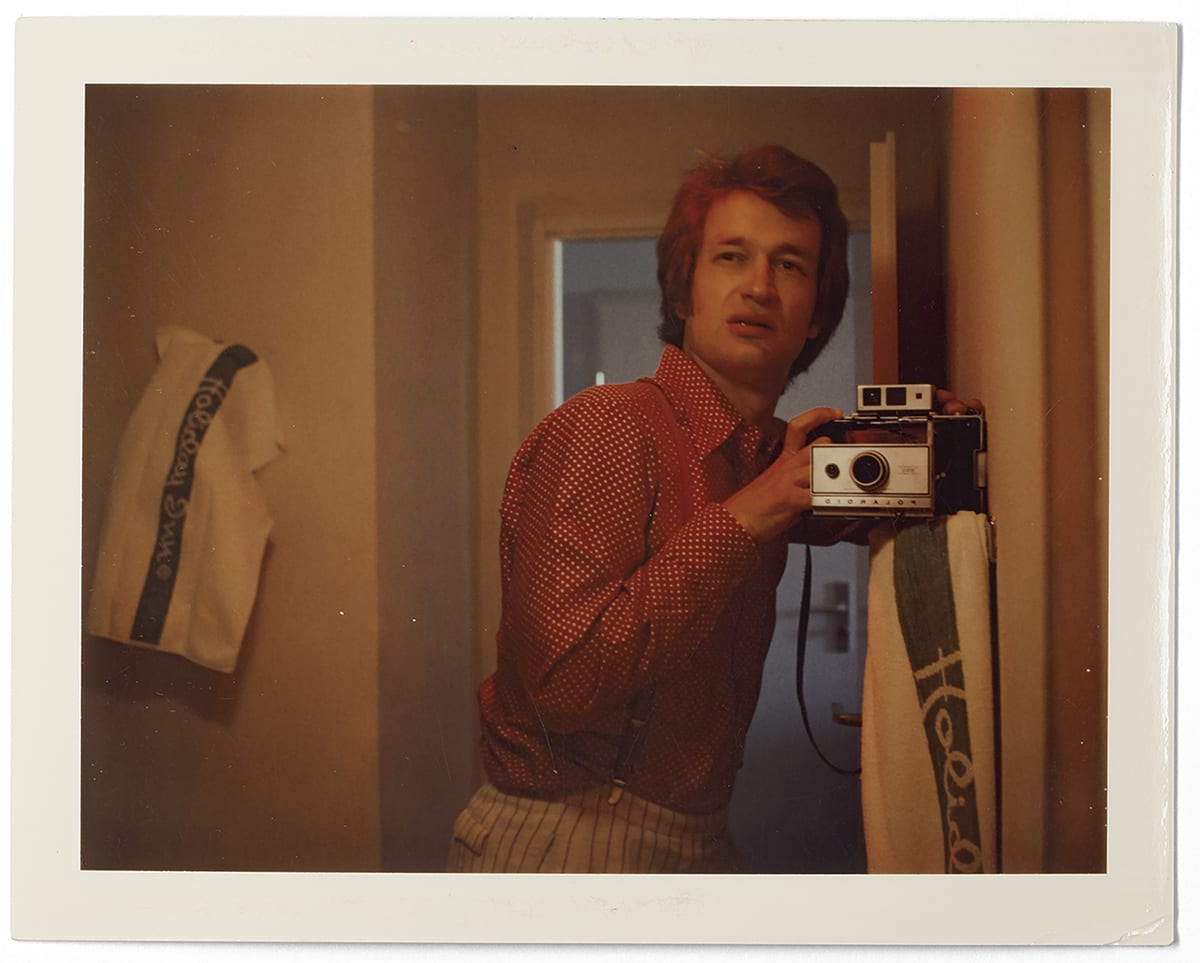

![]()

Zürich around 1961 © Karlheinz Winberger, courtesy Galerie Esther Woerdehoff Paris Photo

We also have Jungjin Lee, which is really more conceptual – between documentary and a really aesthetic response to the landscape. Add to that an installation by Aurélie Pétrel, the newly rediscovered work of Grey Crawford, shot in Los Angeles in the 1970s, and a previously unseen selection of portraits of rockabillies from 1950s Zurich by the extraordinary (now deceased) factory worker cum self-taught photographer, Karlheinz Weinberger.

New this year is MK2, a platform for artists’ film and video, screened in a dedicated 120-seat cinema within the Grand Palais, curated by Matthieu Orléan of the Cinémathèque Française. Partly, it’s recognition that artists are using all kind of media within their photographic practice – “we think it’s important to be more open,” says Wiesner.

But the fair has always been keen to exploit the medium’s close ties with cinema in particular, as evidenced by the three-year run of Paris Photo Los Angeles, (which both repeatedly hint may not be a dead duck). “We had the idea to add video,” says Wiesner. “But video is really hard to display at the fair [particularly in a glass-domed building], because you have to make special booths, and it’s really expensive.”

So the cinema space seemed like an opportunity, and “it was more professional to do it this way,” says Bourgeois. The programme includes a film of Vanessa Beecroft’s performance at Palermo’s Church of Santa Maria dello Spasimo in 2008 , titled VB 62, in which living subjects intermingle with stone figurines to create a tableau vivant, uniting “the arts of time [photography, performance] and the arts of space [sculpture, architecture]”.

Other highlights include Noémie Goudal’s 2013 film shot with the crew of an oil tanker; Hao Jingban’s Off Takes from her five-year research project on the golden eras of Beijing ballrooms; Evangelia Kranioti’s ‘documentary fiction’ set in Rio following the path of transexual figurehead, Luana Muniz; and Roy Samaha’s story of a young Lebanese filmmaker on a trip to Cyprus.

Photobooks are centre-stage once again, with the publisher’s section including 31 stands, where you can meet the likes of La Fabrica, Xavier Barral, RM, Mack and Goliga. Meanwhile, the Paris Photo book prize, run with the Aperture Foundation, is the most anticipated announcement of the fair. Be prepared to give over a good hour or two to browse the shortlist, selected by judges such as Kathy Ryan, erstwhile director of The New York Times Magazine, and 2016 winner Gregory Halpern.

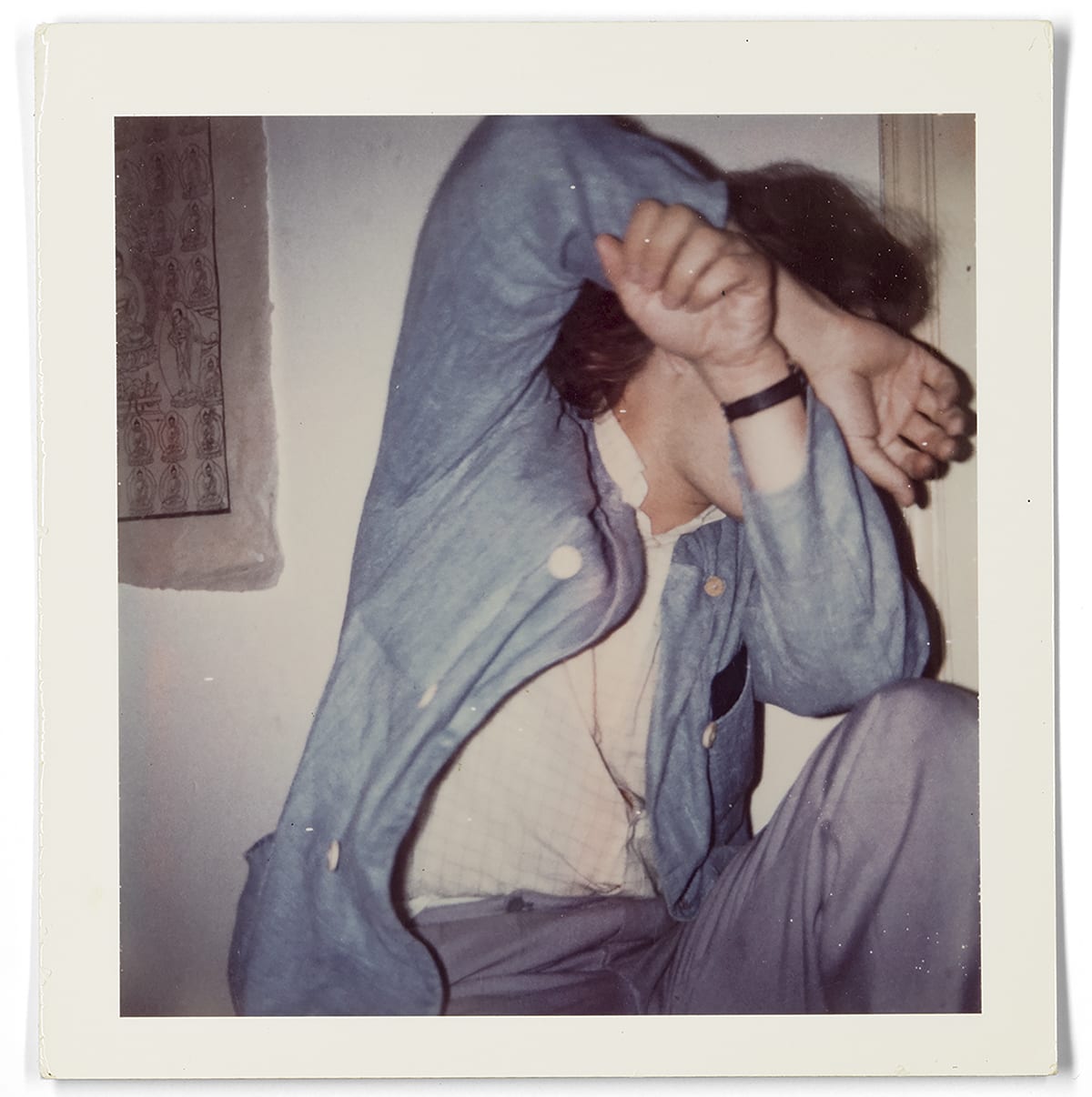

![]()

Self-portrait © Karl Lagerfeld, courtesy Paris Photo

At The Platform, the fair’s talks programme, three guest curators will lead, beginning with David Campany, who’ll chair a day of wide-ranging discussion on the theme of colour including guests such as Harry Gruyaert, Lucas Blalock and Joel Meyerowitz. And among the various partnership programmes, French-American artist Dune Varela will present the results of her BMW Residency at the Museum Nicéphore Niépce, drawing on its collections to “beckon us to places steeped in mythological or mystical meanings that have become part of our collective consciousness”.

The Leica Oskar Barnack Award returns with its latest laureates, including 2017 winner Terje Abusdal, with his multifaceted work on a Scandinavian minority group who maintain a strong sense of identity, despite the disappearance of their language and most of their practices.

In addition, the directors have invited Karl Lagerfeld as guest of honour, asking him to make a personal selection of the displays, by way of creating “a journey throughout the fair and the thousands of artworks”. It is not, Bourgeois assures me, part of some grander ambition to cosy up to the fashion world, of which Paris remains an undisputed capital.

“The DNA of the fair is really [its focus] on the whole panorama of photography, and fashion is only a tiny part of it,” she says. “Karl is a universal artist; he’s a photographer and a fashion designer,” Wiesner interjects. “He’s loved photography for a long time, he collects books, he’s really a character in himself. What is important for us is to get some sort of cross view of the fair from some other perspective – to give visitors a point of view.”

For photography lovers visiting Paris in mid-November, there is much else – too much else! – to occupy hungry eyes. Step outside the Grand Palais at fair time and you’ll immediately be confronted with Irving Penn at 100, The Met’s juggernaut retrospective showing next door at the Galeries Nationales, alongside Gauguin the alchemist.

![]()

Not Miss New Brighton, 1978 © Tom Wood courtesy Sit Down Galerie

The Paris Photo bandwagon has now grown so large that, sensibly, the biannual Mois de la Photo has shifted to spring (and under the artistic direction of François Hébel, widening its scope to the Greater Paris region). Yet there is still room for another photography fair – press.parisphoto, which took up residence two years ago at the Carousel du Louvre, the former home of Paris Photo – and much else besides.

A precursor to Unseen Amsterdam, set up by the granddaughter of French photographer Roger Schall, Fotofever focuses on emerging artists, and has a year-round programme aimed at collectors. Forty-nine galleries were signed up as we went to press, including 18 from France and nine from Japan.

Offprint, at the Beaux-Arts de Paris, 30 minutes walk along the Seine from the Grand Palais, is Mecca for hipster bibliophiles, gathering 120 independent art publishers, with the backing of Maya Hoffman’s Luma Foundation. Along the route, don’t miss Polycopies, another independent book fair (with more focus on socialising and pure photography than Offprint’s mix of trendy graphic design and sometimes poe-faced contemporary art), providing space for 35 publishers across two decks aboard the Concorde-Atlantique.

And in the same neighbourhood, mini festival Photo Saint Germain returns (03-19 November) for its sixth year with more than 40 galleries from the ‘Rive Gauche’, including the Musée National Eugène Delacroix, showing Mohamed Bourouissa, and Atelier Néerlandais, with exhibitions by the Noor collective, alongside Europeans, which puts together Henri Cartier Bresson with Nico Bick and Otto Snoek.

“We are very enthusiastic [about these independently produced satellite events], because it proves the importance of the medium, which is growing,” says Bourgeois. “We think it’s very positive. And on our trend, we are always thinking of expanding our programme, and maybe one day adding other locations.”

![]()

Amanita Fulva, 2017 © Viviane Sassen, courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg PARIS PHOTO

L.A. is continuously referred to, with regret that it only ran for three editions. “We nearly made the fourth. It was done… We would love to come back…. Probably we arrived too early.”

But there is another challenge ahead, when the Grand Palais closes for refurbishment after Paris Photo 2020. “We’ve all been working on this for a year already,” says Bourgeois, referring to the venue and the other faits affected, such as FIAC and Art Paris. Apparently, the mayor of Paris is committed to finding somewhere very central, and extremely attractive.

“It’s not just going to be a little tent,” says a spokesperson who sits with us for the interview. “It’s going to be somewhere quite spectacular.” There are a couple of options already, says Bourgeois, who is determined that it will provide an opportunity to do something different. “It’s a long process that’s taken very seriously. We’ll keep you posted!”